What is the opening of data in practice? What does it require? The OpenFIRE project at the Institute of Seismology highlights the work and expertise needed to open research data, and it also reveals the problems that come along the way.

(Tämä artikkeli on saatavissa myös suomeksi.)

At the beginning of the 2000s, Finnish researchers together with a Russian contractor carried out a large-scale FIRE research project (Finnish Reflection Experiment), which gathered information about the bedrock of Finland. Fourteen years after the research project the data is available for everyone in OpenFIRE web service (see also, Open-access Finnish bedrock reflection-sounding data).

There were two steps in the opening of the FIRE data. The first phase in 2005–2009 represented a ”typical case”, as project manager and former director of the Institute of Seismology Pekka J. Heikkinen puts it.

There were two steps in the opening of the FIRE data. The first phase in 2005–2009 represented a ”typical case”, as project manager and former director of the Institute of Seismology Pekka J. Heikkinen puts it.

”We simply stated that the data is available. After that, anyone who wanted to get the data had to find the right organisation and the right person who was willing to go to the trouble of delivering the data. I do not remember anyone asking for data, or it was only very few who did so,” Heikkinen says.

The consequence of such cursory data publishing is that the data is left unused.

”FIRE is not the only project where a lot of money is used for a field experiment and where the data is exploited relatively little in relation to the investment,” Heikkinen says.

The second attempt – the user in focus

If the first effort in publishing FIRE data represented cursory or apparent data opening, the second attempt can be considered an exemplary case.

The FIRE-ATT project, funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture, started in 2016 at the Institute of Seismology at the University of Helsinki, and its aim was to make the valuable FIRE data easily available to users. A group of researchers and students from the institute was assembled, including Annakaisa Korja and Pekka J. Heikkinen (project managers), Sakari Väkevä (data processing), Aleksi Aalto (software development and user interface design) and Aku Heinonen (geological section of the service).

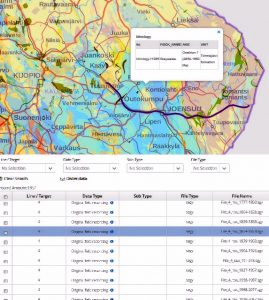

The final product of the project was the OpenFIRE web service, whose beta version was released on the AVAA portal in November 2016. The full version of the service, which provides open access to all original data and processed data products of FIRE, will be published this year.

OpenFIRE is aimed mainly at geological and seismic users. However, the web service takes into account different users, and it aims to lower the threshold for using the data not only in research but also in teaching.

As a data opening project, OpenFIRE’s speciality is its user friendliness. That’s why the service dimension, the commodification of datasets and the user interface design, have been the key concepts in the project.

”Opening data is not just about putting the data on the internet. I think we have to spoon-feed the information to the user all the time. We need to show the user what kind of data we have and what it is used for. The user may not know what he or she is looking for,” Sakari Väkevä explains.

Thresholds of data opening – metadata, money and merits

The OpenFIRE project started because it was understood that the valuable FIRE data should be in active use.

”Based on our previous experience, we knew exactly what the threshold is [in data opening]. It is the data processing. Nobody wants to start that task. It takes a year of work before the raw data is in a condition in which it can be utilised,” Pekka J. Heikkinen says.

”It would be really good if there were clear instructions on what metadata should contain. Then the researcher could create metadata right away [during the research process], and not ten years later. If you do not tend to that troublesome task [of creating metadata] right away, you will not do it later. This is the bottleneck [in opening the data],” Annakaisa Korja says.

There are also other bottlenecks in data opening. The data processing requires work, and funding from the Ministry of Education and Culture was quite crucial for the OpenFIRE project.

”This has taken about a year and a half of work for three persons to make the data open and available on the internet,” Korja says.

According to Korja, the opening of the data is also accompanied by a problem of appreciation, a theme that has been mentioned in the earlier blog posts (see Jouko Väänänen and Mikko Tolonen’s discussion and data citation roadmap).

”The amount of work [in opening the data] is great, but you won’t get any publication points for it. In an ordinary research project the researchers won’t take up the work,” Korja says.

Opening the data requires skills

The Institute of Seismology has a fairly clear view of what the decisive factor has been in the fluent process of opening data. It is the expertise that was available in the institute. In particular, Aleksi Aalto, who was a student when the project started, played a key role because the OpenFIRE service was created in cooperation with the AVAA team.

”I had previously worked as a trainee at CSC’s AVAA projects. I knew how the data is usually opened. It was only natural to join the data opening project in your own field,” says Aalto who works currently in the Institute of Seismology.

”Aleksi had an idea of what is required when this kind of service is launched. It’s pretty unpleasant to think that every research unit should have such a person. But this is what it means when we open data – there must be resources for expertise,” Annakaisa Korja remarks.

”One thing we have learned is that we must be self-contained in expertise. A situation in which you have researchers here and an open data unit – which would take care of the opening of data – somewhere else, would be untenable. I think it wouldn’t work. The data opening cannot be outsourced, because the process would become too slow,” Pekka J. Heikkinen estimates.

One thing we have learned is that we must be self-contained in expertise. A situation in which you have researchers here and an open data unit – which would take care of the opening of data – somewhere else, would be untenable. I think it wouldn’t work.

Was it worth the trouble?

The key benefits of the open data are collective and individual. The benefits include saving resources, increasing the amount of scientific knowledge and advancing science. Open data could also increase the reputation and visibility of the researcher or the research group – or the organisation.

”In many disciplines in Finland, the scientific communities are small. This [data opening] is one way to gain greater visibility and better possibilities for cooperation. If you have something to offer, it is always easier to find friends. The data creator gets benefits, not only in the form of his own publications, but also in the form of citations from other researchers,” Pekka J. Heikkinen says.

”And additionally, this increases the visibility and the significance of the university in this discipline,” Heikkinen adds.

Improved visibility has also been noted in the OpenFIRE project.

”We have been contacted by European researchers who have been interested in FIRE data and the service implementation. In addition, international mineral exploration companies have requested interpretations of the data. Thus, we serve both researchers and society,” Aleksi Aalto says.